Traffic Control Patterns

- RNREDDY

- Sep 9, 2025

- 4 min read

Kubernetes Traffic Control Patterns

One of the first things you learn in Kubernetes is that Pods don’t last forever. They can get rescheduled, restarted, or replaced without warning. So when you want to expose an application running inside the cluster, you don’t point traffic directly to a Pod. You go through a Service.

A Kubernetes Service provides a stable network identity by selecting Pods using labels and exposing them through a consistent endpoint and follows a layered access model.

ClusterIP: Exposes the service on an internal IP accessible only within the Kubernetes cluster, used for inter pod communication.

NodePort: Exposes the service on a static port across all cluster nodes, allowing external access via any node’s IP and that port.

LoadBalancer: Provisions an external load balancer that forwards traffic to NodePort services, providing a single external IP for client access.

Here are four traffic control patterns you’ll often see:

Access With NodePort

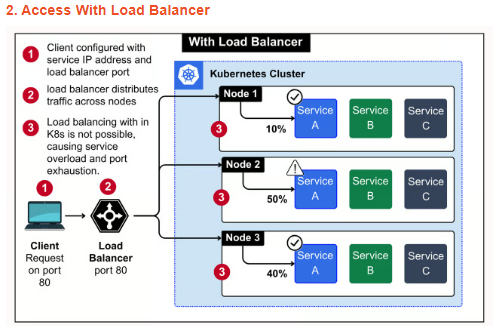

Access With Load Balancer

Ingress Controller managing service routing

Load Balancer combined with Ingress Controller

You’ll usually see this pattern in on prem clusters or early stage cloud setups where a full LoadBalancer integration isn’t available.

But here’s what you really need to know:

NodePort isn’t real load balancing. DNS round robin may seem like a distribution method, but it doesn’t account for node health or service level metrics. If one node is overloaded or down, traffic still gets routed to it.

Clients need to know node IPs and ports. This breaks abstraction. If your client or API gateway is outside Kubernetes, you’re hardcoding infrastructure details into configs. Bad for portability.

Overloaded nodes aren’t just inefficient, they cause failure. Because Kubernetes can’t rebalance incoming traffic across healthy nodes, one node taking the hit can result in failed connections even if pods are healthy on other nodes.

Port range limits matter. You only get 2767 usable ports in the default NodePort range (30000–32767). In clusters with many services or aggressive blue-green deployments, it’s easy to run out.

No SSL termination, DNS based routing, or URL mapping. You’ll have to bolt on those capabilities manually or rely on external proxies, which adds complexity.

If you’re still using NodePort in production, treat it as a temporary bridge. Replace it with a LoadBalancer or Ingress as soon as possible unless you have strict on prem constraints.

This pattern works well for simple setups where you need a public IP without much routing logic. But it gives an illusion of balance.

Cloud load balancers spread traffic across nodes, not across pods. If all replicas of your service land on one node, traffic still hits that node heavily.

Kubernetes Services route internally using round-robin, but only after the request enters the node. So if traffic hits an overloaded node, Kubernetes can’t help much.

You’ll often notice uneven CPU or memory pressure across nodes even when replicas are balanced. That’s because the external balancer doesn’t consider in cluster metrics.

There's no visibility into pod health from outside. A node can be marked healthy while the pods on it are crashlooping. Traffic still lands there.

Teams often assume this is "good enough", until they run into cascading failures under load or unpredictable latency spikes.

This model is okay for simple APIs or one-off services, but if you care about request routing, observability, and scale, you’ll eventually need an Ingress Controller.

This is where traffic handling starts getting smarter. You’re not just exposing services anymore, you’re deciding how and where traffic flows.

Ingress decouples domain logic from infrastructure. You define routing rules in YAML, and the controller handles hostnames, paths, and TLS termination.

It solves the multiple-service exposure problem. You don't need a separate LoadBalancer or NodePort for each service. One Ingress Controller can route to many services.

It is pod-aware. Traffic is distributed directly to healthy pods across nodes, not just at the node level.

You can enforce security at the edge. TLS certificates can be auto-managed with cert-manager, and you can add auth, rate-limiting, or WAFs before traffic reaches your app.

The controller itself is a workload. If not scaled properly, it becomes the bottleneck. Teams often forget to run multiple replicas across zones.

If your cluster hosts public-facing apps or multi-tenant workloads, this pattern is essential. Just make sure your Ingress Controller is built for high availability.

This is the most production ready and widely adopted setup in Kubernetes environments that serve real users or tenants.

A cloud Load Balancer sits at the edge and distributes traffic across Ingress Controller pods running inside the cluster.

Ingress Controllers then apply routing rules and forward requests to the correct service and backend pods, based on domain or path.

This two-level routing gives flexibility at the HTTP layer and reliability at the infrastructure layer.

The Load Balancer takes care of health checks, regional failover, and global IP management, while Ingress handles application level concerns like TLS, redirects, and API gateway functions.

It improves resilience. If one Ingress pod goes down, the Load Balancer reroutes traffic to another healthy pod automatically.

You can horizontally scale Ingress Controllers like any other deployment, making this model easy to scale under load.

If you’re deploying production APIs, multi-domain applications, or tenant-based services, this pattern offers the right mix of control, fault tolerance, and clean separation of concerns.

Comments